We use aggregators (search engines, social media, e-commerce platforms, etc.) as a source of external offer processing. These aggregators are not vendors and they don’t create free markets – they run two-sided marketplaces which capture and sell our attention.

Aggregation

There are many names by which we could refer to these corporations. For a while I called them ‘offer-processing corporations’, but that was a mouthful. I’ve decided to follow Ben Thompson’s lead in calling them aggregators, based on the verb to aggregate:

Aggregate (verb): To bring together; to collect into a mass or sum.

This has a useful double meaning. The first meaning refers to the main business activity of aggregators – to aggregate offers in order to process and represent them to us in maps. As we explore this problem, however, we’ll discover the second meaning, that aggregators are in the business of aggregating our money, efficiency and opportunities.

Firstly, however, we need to understand what aggregators are not.

Aggregators are not vendors

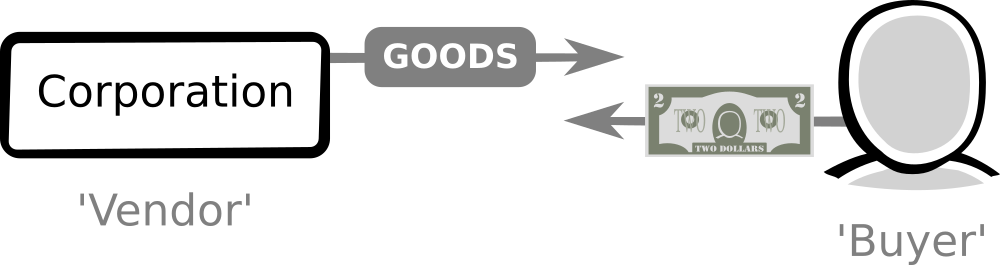

Most corporations in our economy act as vendors – they offer us a simple exchange in which they supply us with goods when we supply them with money:

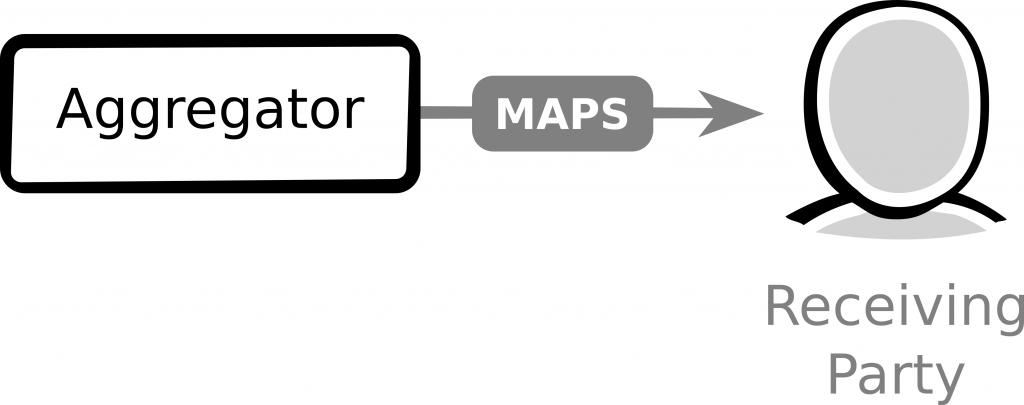

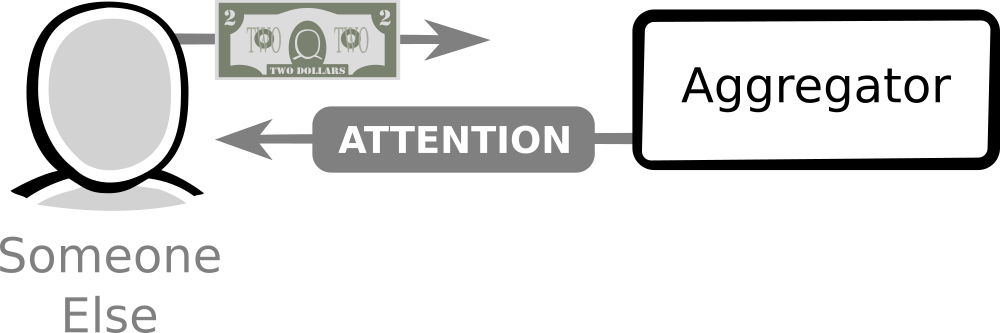

Aggregators, however, don’t appear to work this way. Consumers don’t pay a cent per search to Google, a few dollars per month to Facebook or an entry fee to shopping malls. None of these aggregators corporations ask us for money – they simply give us their maps in an interaction that looks like this:

This begs an important question – if receiving parties don’t supply money to the offer-processing corporation, how does the corporation collect money (and collect so much of it)?

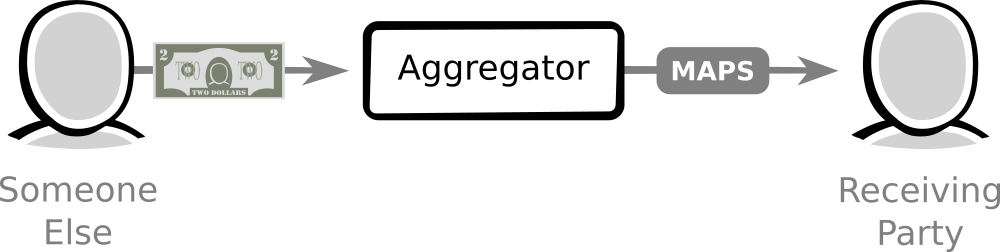

Clearly someone else must be giving them money:

But why would someone else give their hard-earned cash to the corporation? The corporation must be giving them something valuable for their money (and this valuable thing must involve the receiving parties, or the corporation wouldn’t generate maps).

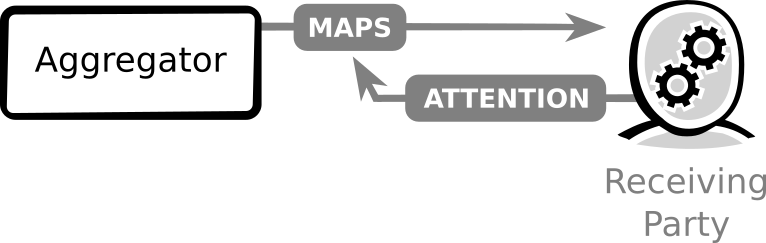

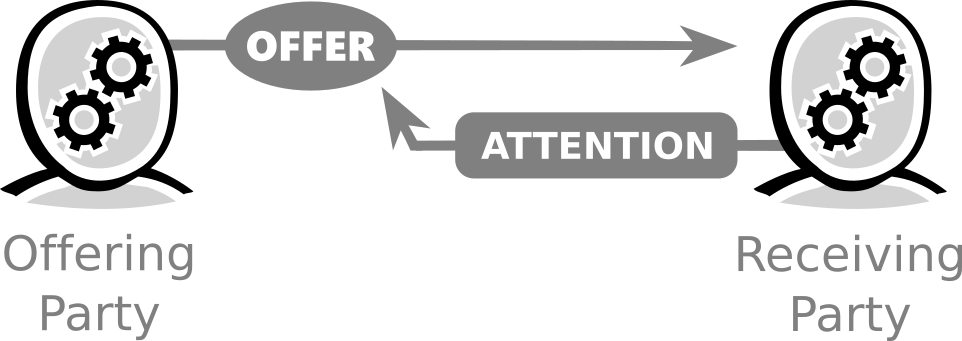

The answer is that we missed something when looking at the interaction between offer-processing corporations and receiving parties. The corporation isn’t simply giving us a map – they’re exchanging it for our scarce attention:

That is, offer-processing corporations generate maps which conserve our attention as we look for offers so that they can capture our attention to maps which represent offers.

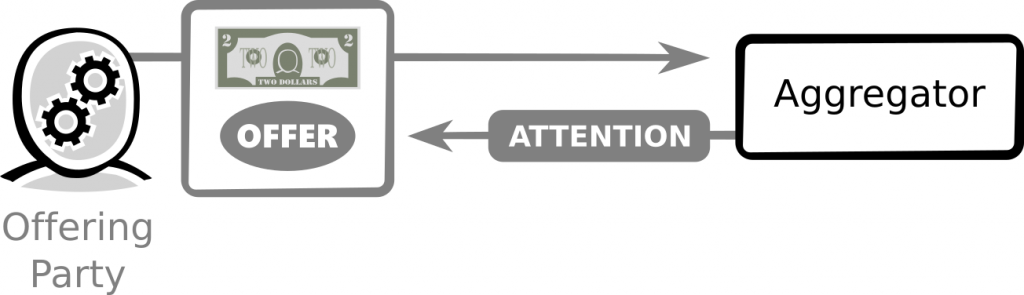

This allows the corporation to sell our captured attention to someone else:

Now we need to identify this someone else – who wants receiving parties’ attention badly enough to pay for it? The answer, of course, is that offering parties need the attention of receiving parties to be drawn to their offers (so that their offers can be received and both parties can interact with each other in valuable ways):

Offering parties are willing to pay the corporation, therefore, because the corporation has captured receiving parties’ attention to their maps. In a process that we call advertising, corporations bring receiving party attention to the offers of people who pay them:

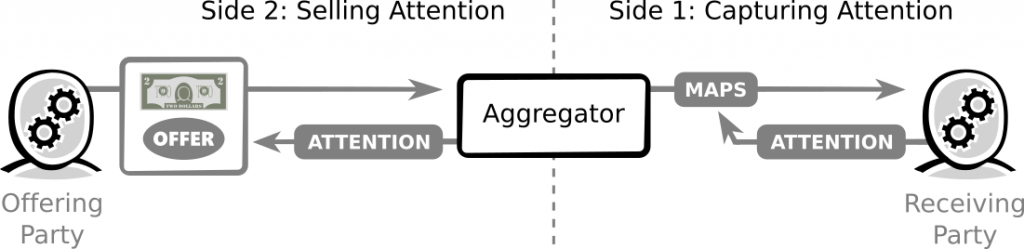

Putting all that together, we can see that aggregators run a two-sided market where one side is capturing attention and the other side is selling it:

Now that we know what aggregators are doing, the next question is why they’re doing it.

Why sell attention?

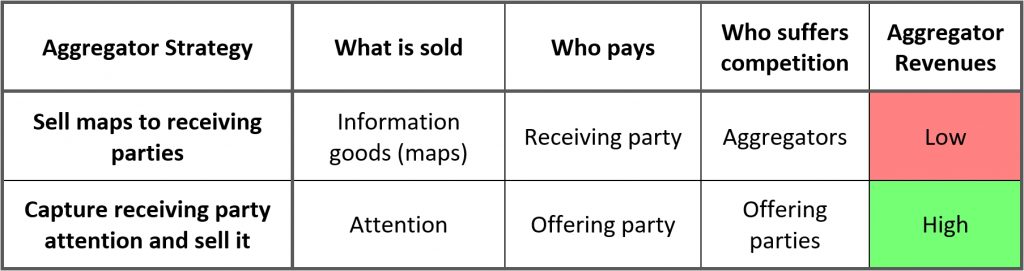

Why do offer-processing parties run two-sided markets (capture receiving parties’ attention and sell it to offering parties) when they could simply act as vendors (selling maps to receiving parties)?

The answer is found in the concept of scarcity. Corporations which sell abundant resources open themselves to significant competition from other corporations and this competition drives their prices and profits downward. Corporations prefer to sell scarce resources, therefore, because this scarcity prevents other corporations from obtaining those resources and competing with them.

The strategy of capturing attention and selling it to offering parties, therefore, is a vastly more profitable business than simply selling maps to receiving parties. That’s because the abundance of processing power, bandwidth and storage means that almost any corporation can generate maps and, therefore, that maps can become an abundant resource. Our attention, however, is scarce and selling it is more likely to generate significant profits.

The nature of our attention, however, makes its scarcity even more significant. Our attention can be given to only one map at a time, meaning that the corporation who generated that map has, at that exact moment, an absolute monopoly over the receiving party’s attention. For as long as the receiving party gives their attention to a map, there is nowhere else that an offering party can go to buy attention for their offer [1]. By pursuing an attention-based strategy, therefore, offer-processing corporations can literally hold our attention for ransom from the offering parties who desperately need our attention to be given to their offers.

That is, the corporation’s monopoly can be used to shift the locus of competition. Instead of the corporation suffering competition, the corporation can instead force offering parties to compete with each other, whether by entering bids into an auction system (e.g. Google AdWords) or by responding to prices set by traditional media [2], to pay the highest possible price [3] for receiving party attention. This allows the offer-processing corporation to extract a significant proportion of the value exchanged between the offering and receiving parties who trade using as they trade with each other through the corporation’s maps.

For profit-maximizing aggregators, the choice of strategy is simple:

This is why maps are made ‘free’ to receiving parties when new technologies (such as the web) reduce the marginal cost of delivering those maps – there’s no point attempting to collect small payments from receiving parties as this would be a barrier to collecting large payments from offering parties.

But how do aggregators sell our attention to offering parties?

How our attention is sold

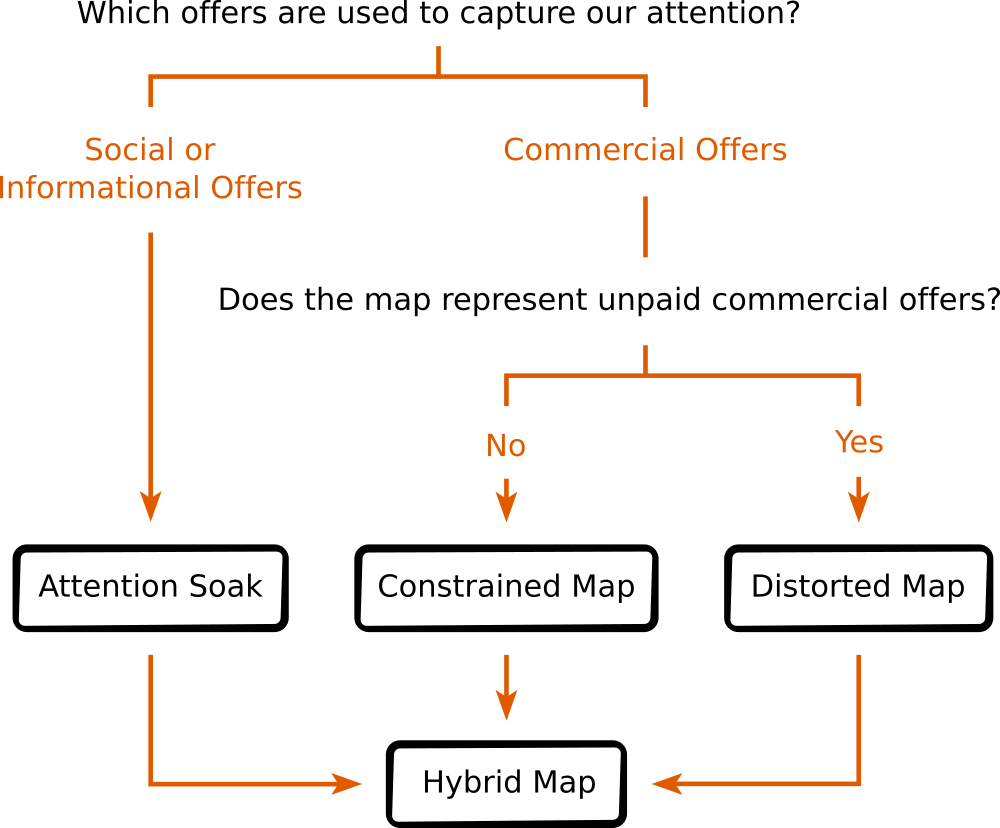

If aggregators simply sold us maps, their incentive would be to generate the most helpful maps (because those are the maps we’d pay the most to use). Because they’re in the business of capturing and selling our scarce attention, however, their incentives are entirely different – their maps must manipulate our attention as receiving parties so that offering parties can be forced to pay the corporation.

The only way to do this is to generate maps which lie to us about our economic, social or informational territory. There are four different types of maps, each with their own perverse incentives and lies:

Each type of map is described briefly below, with a link to an article if you’d like to learn more.

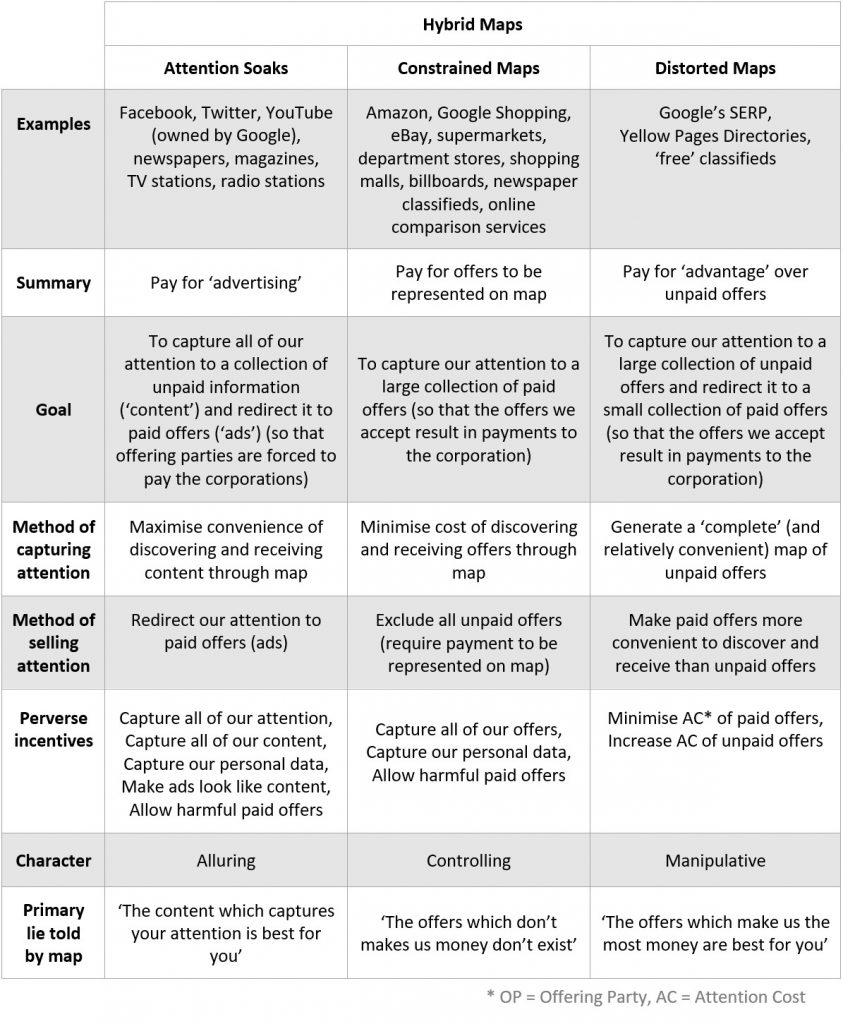

Attention Soaks

The most common type of map (including newspapers, magazines, radio, television, social networks, etc.) attract our attention to social and informational offers and sell it through advertising (the representation of paid commercial offers). These maps lie to us about which offers (social, informational and commercial) are best for us.

Learn More: Attention Soaks

Constrained Maps

E-commerce sites, supermarkets, shopping malls and some classified sites are constrained maps – they attract our attention to paid commercial offers (ads) and do not represent unpaid commercial offers. These maps lie to us about which commercial offers are best for us.

Learn more: Constrained Maps

Distorted Maps

Search engines, Yellow Pages directories and ‘free’ classifieds are distorted maps – they attract our attention to free commercial offers and redirect it to paid commercial offers by manipulating the attention cost to receive paid and unpaid offers. These maps lie to us about the commercial offers which are best for us (and lie about being ‘free’ and open to everyone).

Learn more: Distorted Maps

Hybrid Maps

Many aggregators use multiple strategies at once. Amazon, for instance, is a constrained map but it also adds a layer of distortion by inviting offering parties to pay more to stand out from the competition. LinkedIn is a constrained map for job ads and an attention soak for employees.

Summary of map types

It’s also worth noting that there are aggregators who don’t sell our attention because they haven’t worked out how to do it yet or their primary goal is to build a user base and be acquired by a larger aggregator. [4]

Aggregators are not markets

At this point, some attentive people may have two objections:

If free markets allocate scarce resources, isn’t attention just another scarce resource to be allocated by free markets?

On that basis, who could possibly object to aggregators selling attention in a free market (to the highest bidder)?

The answer is that attention isn’t just another scarce resource – it’s the only scarce resource which enables the free market. Offers must be processed for markets to be created (for supply and demand to meet each other) and receiving parties must use their attention to process offers found on aggregators’ maps [5].

It follows that selling attention captured by a map will damage the market created by the map. The evidence is in the distortions induced by aggregators to sell our attention in each type of map (attention soaks, constrained maps and distorted maps). The markets created by aggregators cannot be free markets because the buyer’s choice of vendor is constrained and manipulated by the aggregator to maximize their profits.

It’s time that we faced an uncomfortable truth. If aggregators are not vendors and they’re not our markets, they’re our competitors.

Next: Techno-Kleptocracy

Footnotes:

1. Note that it doesn’t matter how long the attention is held for, whether that’s hours (e.g. TV) or seconds (e.g. Google’s Search Engine Results Page) – at that moment there is no competing corporation from whom the offering party can buy the receiving party’s attention.

3. Note that traditional media have been in the game long enough to know the maximum price they can set for their advertising space, meaning that competition between offering parties is already ‘baked in’ to the price.

3. Google would likely object to their AdWords auction being characterised as extracting the ‘highest possible price’ as their Ad Ranking also takes into account a Quality Score (which assesses the relevance of each ad to prevent a less relevant ad from obtaining the top ranking, even if the bid is higher). I would argue, however, that this is still the ‘highest possible price’ because the limit of what price is ‘possible’ is our lack of interest in irrelevant advertising. In all other respects Google does everything it can to make offering parties pay the highest amount which is, principally, to maximize the number of people bidding for each keyword (see The Economics of Internet Search by Hal Varian, Google’s Chief Economist).

4. The strategy for aggregators is to attract user attention first and then sell our attention later (and it’s a trap – a free and generous map! – that we fall for every time). Here’s what Marissa Mayer said about this strategy when she was a VP at Google (my apologies for the long quote but it’s worth reading): “Users, not money. It’s interesting. You know, now I think people understand how Google makes money. In the early days, people say, you know, the first question at any talk like this would be, from the audience, would be, “How does Google make money?” And, you know, a lot of people will say, “Well, aren’t you worried as you roll out new products, you know, will there be a business model there, you know with all this innovation?” And to be honest, we don’t really worry about that. We worry a lot about whether or not we have users, but we don’t worry a lot about business models in the beginning, because it turns out, especially on the Web, and especially with consumer products, money follows consumers. The consumers may choose to subscribe to things themselves. Advertisers also follow consumers, so if you manage to amass huge amount of users and you’re doing something that they use every single day, you’ll find a way to monetize it. You know, this is sort of the “if you build it, they will come” strategy. […] if you’re really successful and you get used a lot, there’s usually a very easy and obvious way to figure out how to monetize it.”

5. This is one of the reasons that aggregators ban users from using bots to access (scrape) their maps – the maps are designed to manipulate attention costs for buyers to direct them to advertising. When processing power is more abundant (via a bot), the user is less likely to be manipulated and the aggregator is less likely to make money.