We interact with other humans by making offers to them. These offers consume our attention, making it scarce. This prevents us from finding the best offers (and participating in our economy, society and information).

Interactions require offers

As humans, we want to interact with other humans. We do this by making offers.

When we make an offer, we’re inviting another person to interact with us in a particular way. For instance, we might invite other people to:

- buy our product or service,

- attend our event,

- work for our company,

- look at our photos,

- borrow a book or movie,

- read a status update, blog post or web document, or

- have a conversation with us.

We make an incredibly diverse range of offers to other people. We could break these offers down, however, into three broad categories:

- commercial offers – the invitations to enter into profit-making interactions (trade), the sum of which we call our economy,

- social offers – the invitations to interact in a manner which builds relationships, the sum of which we call our society, and

- informational offers – the invitations to access an information source, the sum of which we call our information in its broadest sense.

We could say, therefore, that our offers are the organising principle around which our economy, society and information are built.

This means that the process of making and receiving offers is of first importance – something that we should pay close attention to if we care about our economy, society and information. Our familiarity with the process of making and receiving offers, however, means that we give it little thought.

In particular, we fail to notice how difficult it is.

Offers are represented as information

Offers originate somewhere in our minds when we realise that we’d like to interact with another person.

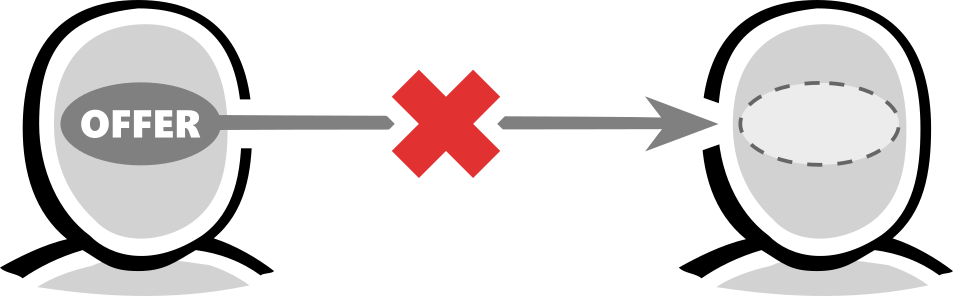

We can’t interact with that person, however, unless they know what we’re offering them. This creates a problem because our brains are not like networked computers – we can’t copy an offer from our brain to another person’s brain:

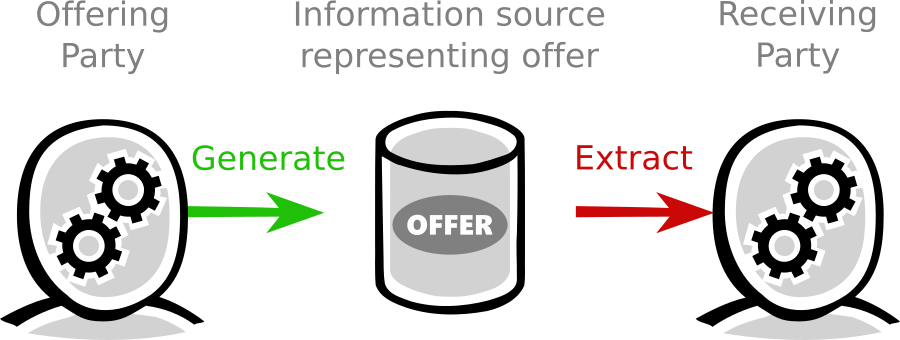

Instead, we must somehow represent our offer as information that the other person can receive. Specifically, the offering party (OP) must use their attention (their real-time mental processing power [1]) to generate an information source which represents their offer. Then the receiving party (RP) must give their attention to that information source in order to extract the offer’s structure and attributes and, therefore, understand what’s being offered to them:

The process of generating an information source and extracting meaning from it comes naturally to us. We do this constantly in conversation with people (as we work out what to say and determine what other people have said to us):

It’s a straightforward task, therefore, to generate some speech which represents an offer of any type, whether it’s a:

- commercial offer (‘would you like to buy this book?’),

- social offer (‘will you come to our house for dinner tonight?’), or

- informational offer (‘would you like to know the history of our town?’):

If we could look inside each person’s head to see how the information flows there, we might see something like this (which will become a useful model for us later):

That is, the underlying goal of this process is for the receiving party to store this offer in their memory so that they can compare it against:

- their needs and wants (e.g. ‘Do I want to learn the information in this book?’), and

- other offers in their memory (e.g. ‘Does this price seem reasonable compared to offers of similar books?’).

Then the receiving party can either:

- accept the offer (interact with the other person by buying their book),

- store the offer (remember it for another time), or

- reject the offer (by giving it no more attention or memory).

Conversation is, therefore, a useful method for making any kind of offer to any person who speaks the same language. The nature of conversation, however, is that it requires:

- proximity (both parties must be present in the same location),

- synchrony (both parties must be present at the same time),

- permission (the receiving party must be willing to engage in the conversation), and

- politeness (both parties are delayed by the additional conversation required by social norms – e.g. ‘How have you been since I saw you last?’).

Making offers through conversation is therefore quite inefficient, because the offering party must participate in a face-to-face and end-to-end social interaction with each person they make an offer to. Within a small community this inefficiency is highly desirable – conversations build relationships between the people of that community – but in a large or constantly-changing community this inefficiency becomes a barrier to interacting with others.

What we’ve seen, therefore, is that as our village-based communities have become global ones, we’ve adopted more efficient methods of conveying information which remove the need for proximity, synchrony, permission and politeness from the offer-making process.

In short, we’ve adopted various media to represent our offers.

We use media to represent offers

We use various information technologies – signage, print, radio, TV, email, the web and personal devices – to make offers to each other.

The efficiency of media means that each person can make offers at scale – to tens, thousands or even millions of people – without participating in tens, thousands or millions of inefficient conversations. All the offering party needs to do is:

- use their attention to generate a single representation of their offer, and

- bring the attention of other people to that representation:

And there, as you well know, we have a significant problem.

Information consumes our attention

The flipside of being able to make offers at scale, of course, is that our attention is now being captured to many different representations of offers from many other people:

This makes our attention scarce because:

- information consumes our attention [2], and

- we have a limited amount of attention to consume.

What we need to recognise, therefore, is that we can receive only a tiny proportion of the offers that other people could make to us.

Consider for a moment what offers you’d be willing to make to other members of the public. You might have hundreds of status updates, photos, blog posts, opinions, web documents or other digital content that you would like to share with them. You have labour that could be sold to employers. You might have products or services to sell. Or perhaps you have second-hand goods that you want to get rid of, a garden which produces more fruit than you need or tools you’re willing to share. Whatever it is that you’re willing and able to offer to other people, chances are that there are tens, hundreds or even thousands of offers that you could make to other members of the public.

Now consider that there are several billion people and millions of corporations around the globe, each of whom could make tens, hundreds or thousands of offers to the public. Multiplying the number of offers per person by the global population tells us that there could be hundreds of billions or even trillions of offers that could be made to you by other people.

We can now guesstimate just how small this tiny proportion of offers is. Even if:

- each of us could receive and consider a thousand offers per day (which we probably can’t),

- each of those offers were unique (which they’re not), and

- we could remember every offer we every received (which we can’t);

it would take each of us a few thousand lifetimes to receive all of the offers which could be made to us right now.

This begs an important question – if we receive so few of the offers which could be made to us, how can we possibly find the best offers?

We can’t find the best offers

Attention is not our only scarce resource. Many of the other resources that we have – notably our time, energy and money – are also scarce. To make the most of these scarce resources, we want to find and accept the offers which are ‘best’ for us in the situations we find ourselves in. The problem is that the ‘best’ offers are the proverbial needles in a global haystack, lost somewhere in that vast sea of offers made to us.

We find ourselves, then, in a catch-22 situation:

- we want to preserve our scarce attention by allocating it only to receiving the ‘best’ offers (by ignoring all of the offers which are not the ‘best’), but

- the only way to work out which offers are ‘best’ is to give our attention to every (or, at least, many) offers.

In short, the only way to conserve our scarce attention is to spend a great deal of it. You and I don’t have enough attention (let alone the memory, desire and patience) to receive many offers and determine which are best.

You and I can’t, therefore, process our own offers. We need external offer processing to help us.

next: External Offer Processing

Footnotes:

[1] Attention and time are related to each other in this way: Any task which requires our attention also requires our time (e.g. reading a brochure to receive an offer). Tasks which require our time, however, do not necessarily require our attention (e.g. being put on hold when calling a company).

[2] “…in an information-rich world, the wealth of information means a dearth of something else: a scarcity of whatever it is that information consumes. What information consumes is rather obvious: it consumes the attention of its recipients. Hence a wealth of information creates a poverty of attention and a need to allocate that attention efficiently among the overabundance of information sources that might consume it.” Simon, Herbert. A. (1971). Designing Organizations for an Information-Rich World.