Because offers consume our attention, we need an external form of offer processing. That is, we need maps which represent our economy, society and information so that we can navigate them with the attention available to us.

External Offer Processing

For the reasons outlined in Offers & Attention, you and I need offer processing which is external to our brains. We need someone (or something) with an abundance of processing power to preprocess offers on our behalf.

Specifically, we need this external processing to:

- receive the offers (the information sources which represent offers) made to us,

- store them in memory or a database,

- consider (filter, compare, rank, etc.) these offers on our behalf, and

- represent the ‘best’ offers by generating a single information source – a map, if you like – that we can use to navigate our economy, society and information:

If this seems familiar, it’s because this is the service that Google, Facebook, Amazon, Yellow Pages directories, newspapers, supermarkets, shopping malls, online marketplaces and many other corporations perform for us. They use the processing power of many humans and computers to:

- receive, store and consider offers on our behalf, and

- generate maps in various media (web documents, emails, app views, printed material, the shopping mall itself, etc.) which represent the ‘best’ offers to us.

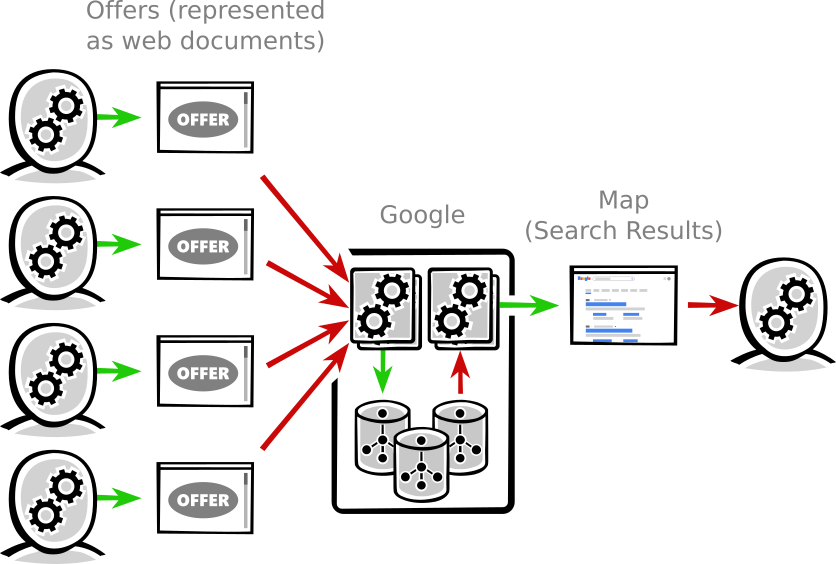

Google, for instance, crawls the web (gathering the commercial, social and informational offers represented in public web documents) and ranks these offers to generate a Search Engine Results Page (SERP) – a map which represents the ‘best’ of the offers made to us:

What, then, are maps and why are they useful to us?

Maps

Maps are simple representations of complex territories for performing a particular task [1].

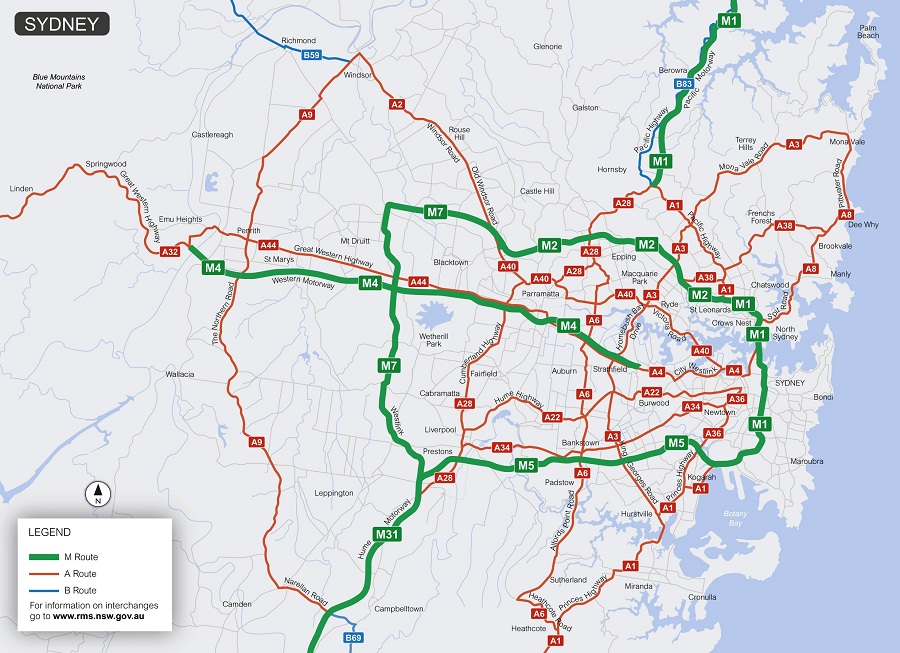

Consider, for instance, this road map of Sydney, Australia:

This map is a simple representation of Sydney for the task of traveling across the city. It’s simple because it excludes the vast majority of the city’s complexity – it filters out the buildings, electrical infrastructure, sewerage, flora, topography and countless other attributes of Sydney. It even ignores most of the city’s minor roads so that the reader can, with a low attention cost, identify the major roads which permit travel from one side of Sydney to another.

The simplicity of a map like this, relative to the territory it represents, explains why we give our attention to maps. They help us to lower our attention costs by allowing us to process the simple map rather than process the complex territory.

In other words, the existence of the road map (and of other maps such as road signs, street directories, satellite navigation, etc.) eliminates the need for visitors to waste time trying many different roads to see where they go. Instead of discovering and processing each road, visitors to Sydney can simply discover and process this map.

The same principles apply to maps of more ephemeral territories – our economy, society and information.

Maps which represent offers

Maps of offers free us from the task of processing the economic, social and informational territory ourselves. Instead of processing the territory (all of the offers made to us in our economy, society and information) we can instead process the best offers, those which are represented to us in the map. [2]

Like maps of physical territories, maps which represent offers can be simple because they’re generated for a particular task (e.g. finding a job), allowing the exclusion of offers which are outside of that task (e.g. offers of sports equipment).

For example:

- Facebook is for connecting with friends (and represents only information offered by our friends),

- a shopping mall is for buying products and personal services (and does not represent any other kind of offer),

- the Uber app is for finding rides (and represents only rides from its drivers),

- a newspaper is for being informed and entertained (and its editor selects articles which are likely to inform and entertain its readers),

- Yelp is for deciding which business to use (and represents only offers from businesses and reviews of those businesses), and

- Google Search is for finding a website relevant to your query (and excludes every irrelevant website).

We give maps our attention, then, because they do two amazing things at once – they:

- conserve our attention (compared to processing the territory), and

- provide access to new opportunities to interact with other people (which we otherwise could not find).

That’s why we use Amazon, Google, Facebook, supermarkets, Twitter, Instagram, YouTube, AirBnB, AliExpress, shopping malls, Twitch, TikTok, The New York Times, Reddit, Booking.com, Pinterest, Uber Eats and many, many other maps.

It’s also why these maps (and the external offer processing behind them) are the key enabler for interactions in a complex world. Maps create the opportunities for us to interact and the markets in which we trade.

It’s important that we pay attention, therefore, to the corporations which generate these maps. From now on, I will refer to these corporations as aggregators.

Footnotes:

[1] “Two important characteristics of maps should be noticed. A map is not the territory it represents, but, if correct, it has a similar structure to the territory, which accounts for its usefulness. If the map could be ideally correct, it would include, in a reduced scale, the map of the map; the map of the map of the map; and so on, endlessly …”. Korzybski, A (1973), Science and Sanity: An Introduction to Non-Aristotelian Systems and General Semantics (5th ed.). Institute of General Semantics.

[2] In (Stigler, 1961, p. 216), George Stigler wrote that: “The costs of search are so great […] that there is powerful inducement to localize transactions as a device for identifying potential buyers and sellers” and then provided medieval markets as an example of this kind of localisation. In using the term ‘map’ I’m referring to any information source (such as a medieval market) which localises offers to a single information source. Using this generic term allows us to discuss the concept of localising offers (or rather, localising the representation of offers) without being tied to any particular medium or point in history.