Attention soaks capture our attention to non-commercial offers and sell our attention to paid commercial offers (advertising). These maps have several perverse incentives and lie to us about the offers which are best for us.

A familiar map

Attention soaks are the most familiar maps because we’ve been surrounded by them all of our lives. Examples include newspapers, magazines, radio stations, television stations and social networks (Facebook, Twitter, YouTube, etc.).

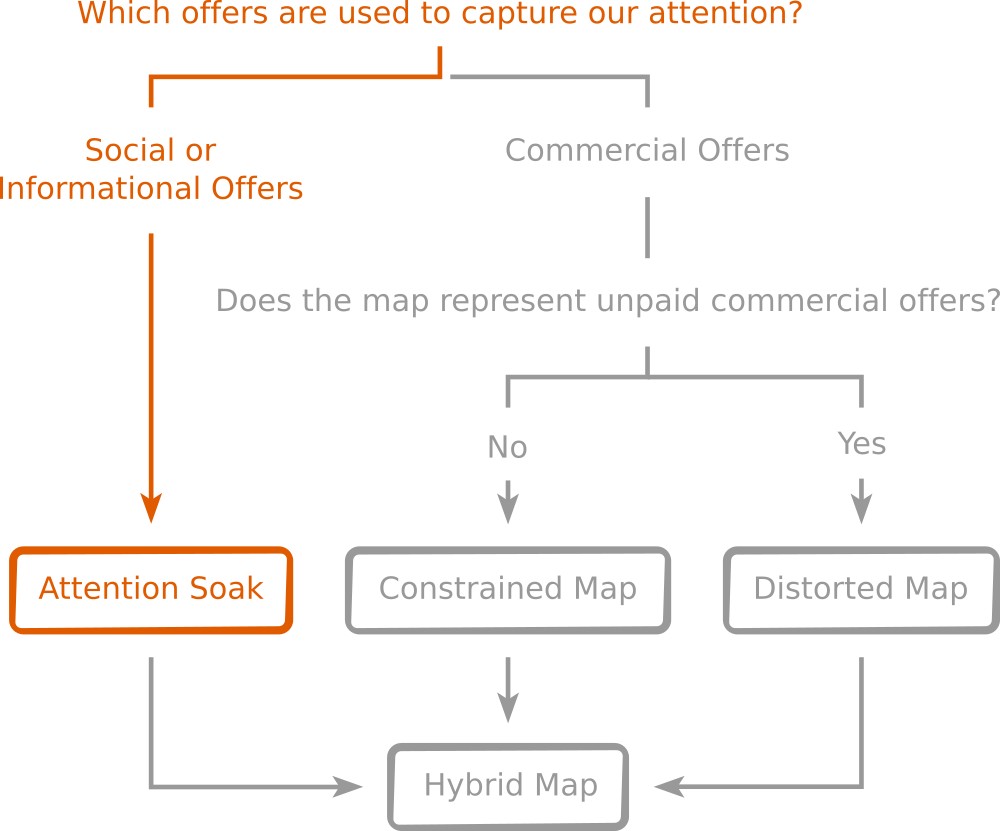

Attention soaks maps gather and represent social and informational offers – offers of images, videos, status updates, television programs, news articles, invitations to events, etc. (which we often refer to collectively as content):

The purpose of generating this map is to soak up our attention, to capture as much of our attention for as long as possible. Anyone wanting to make commercial offers to these receiving parties (whose attention has been captured by the map) is therefore forced to pay these corporations so that receiving party attention can be directed toward their offer.

We normally call this advertising.

How attention is captured

Attention soaks capture our attention by doing all of the processing tasks (finding content, curating it and generating the map) necessary to bring social and informational offers together into a single map (the social media feed, printed newspaper, television feed, etc.). We give our attention to attention soaks because they reduce our attention cost in finding content that is interesting (worth paying attention to).

Television stations, for instance, employ media buyers who identify and negotiate rights to the best content, schedulers who will work out when to show it and technical staff and equipment to broadcast their feed, allowing us to simply vegetate in front of our televisions.

Or consider Facebook – their application encourage us to supply the content for free so that Facebook’s servers can generate maps of our content for our friends. We use Facebook, therefore, because it offers the lowest attention cost in making and receiving social and informational offers with our friends (compared, say, to the attention cost of telephoning each of your friends to tell them your latest news or sending pictures to each of them via email).

Aggregators also acquire our attention from other maps which have captured it. In 2019, for instance, Google paid $30B in ‘traffic acquisition costs’ to AdSense Publishers (web publishers who run Google display advertising on their attention soaking-websites) and other corporations (such as Mozilla and Apple who were paid to make Google Search the default search engine on their web browsers).

How attention is sold

The strategy for selling attention on attention soaks is relatively simple – it’s to represent paid commercial offers (advertising) alongside the social and informational offers (content) in a way that redirects receiving parties’ attention toward the advertising. Or to put it in the negative, our attention is sold by excluding all unpaid commercial offers so that offering parties making commercial offers must pay to receive our attention:

What the aggregator is selling to the offering party (the vendor), therefore, is a temporary monopoly on receiving party attention. That is, each receiving party sees the offer outside of a market (where the receiving party might compare it with competing offers), allowing the offering party to raise their prices.

The aggregator can then maximize competition for offering parties to purchase this temporary monopoly, typically by auctioning off the advertising space, allowing the majority of the offering party’s surplus (from the increased price) to be transferred to the aggregator.

It’s worth noting that some offering parties will be able to disguise commercial offers as content (which we call organic reach – the use of PR, content marketing, native advertising, etc. to represent commercial offers on attention soaks without paying the aggregator). It is, however, in the aggregator’s interest to close down opportunities for organic reach and Facebook is succeeding in doing this.

Perverse incentives

The perverse incentives for corporations adopting an attention-soaking strategy are to:

- capture content exclusively to their map (so that it cannot be found on competing maps),

- capture all of our attention [1] by capturing all of our content (e.g. Facebook).

- capture our content so that the corporation doesn’t need to pay for professionally-generated content (and can even sell our content to other offer-processing corporations [2])

- capture our attention by any means necessary (e.g. fear-mongering, superficiality, sexualization, sensationalism, misrepresenting reality, etc.)

- capture private information about receiving parties to make paid offers more ‘relevant’ and, therefore, more profitable (e.g. Facebook, Google AdSense, etc.),

- make paid offers look like content so that we are tricked into receiving them (a.k.a. native advertising), and

- allowing offering parties to represent their paid offers as they see fit (in the best possible light), regardless of the offers’ impact on us (on our society, environment, workers, etc.).

Attention soaks, therefore, are designed to be so alluring that we want to use them all of the time and, where the underlying technology of the map permits, we want to give our personal content and information to the corporation. Then offering parties and their money must follow.

The lie which attention soaks tell

The first lie which attention soaks tell us is that that:

The content which captures your attention is best for you.

The second is:

The commercial offers which make aggregators the most money are the best commercial offers for you.

Footnote:

1. “In the world of tech, we compete [with other tech companies] for every minute of your attention.” Sheryl Sandberg, COO of Facebook at 47:48 of a podcast episode with Dylan Byers (and as reported by News 18).

1. Twitter currently makes 13% of its revenue from selling our tweets to other parties