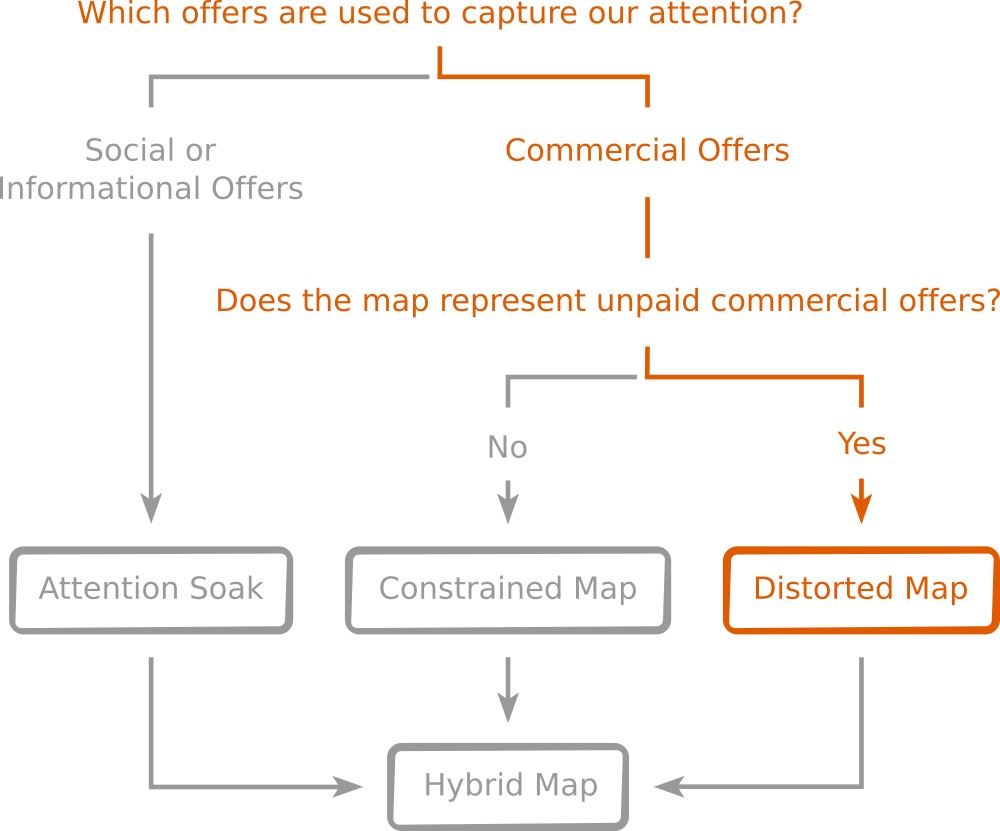

Distorted maps capture our attention to unpaid commercial offers and redirect it to paid commercial offers by manipulating the attention costs of receiving the offers. These maps have several perverse incentives and lie to us about the offers which are best for us.

Unpaid commercial offers

Distorted maps are similar to constrained maps in that we use them to receive commercial offers. Unlike constrained maps, however, distorted maps also represent unpaid commercial offers:

Examples of distorted maps include the Google Search Engine Results Page (SERP)[1], Yellow Pages directories[2] and ‘free’ classifieds.

How attention is captured

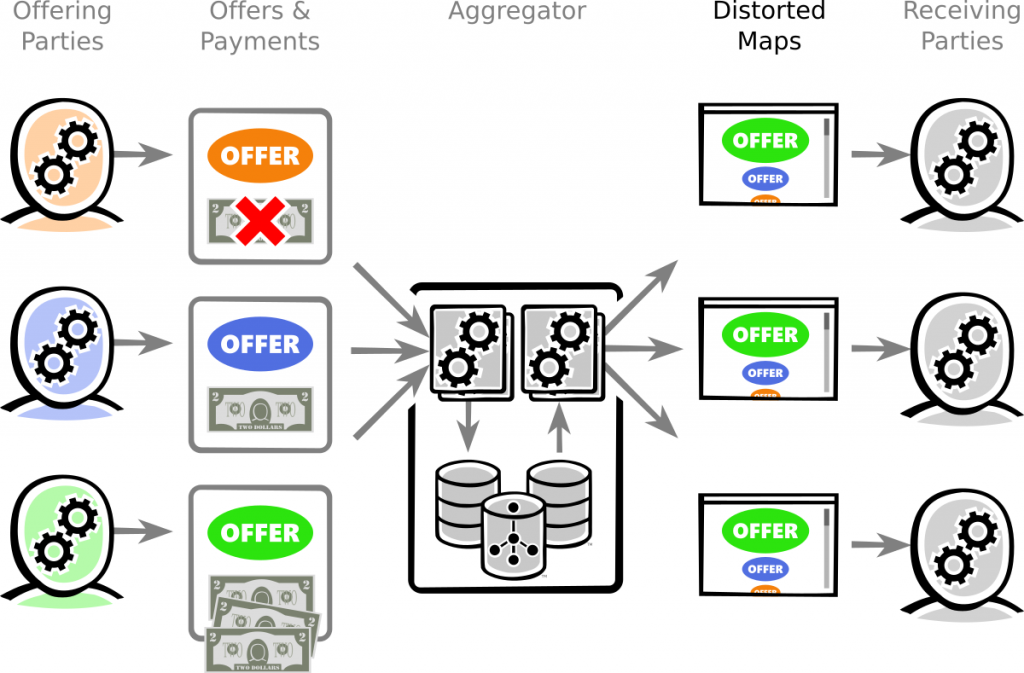

Distorted maps capture our attention by offering us a complete map – a map which appears to represent every offer, both paid and unpaid. Google Search, for instance, scans every web document (and therefore every offer represented) on the public web, and Yellow Pages directories give a free entry to every service provider in a city.

This completeness provides a ‘one stop shop’ – a single map which appears to cover the entire territory and, therefore, is preferred by receiving parties who want to avoid the attention cost of using multiple constrainedmaps (which are not complete because each map excludes many unpaid offers).

The distorted map strategy also avoids the chicken and egg problem[3] that aggregators starting a constrained map have – they can attract all of the offering parties who are tired of paying constrained maps for every scrap of our attention.

How attention is sold

When it comes to selling our attention, however, distorted maps have a problem that constrained maps do not. On a constrained map, it doesn’t matter to the aggregator which offers receiving parties accept because every offer represented on the map is paid (makes revenue for them).

On a distorted map, however, it does matter to the aggregator which offers the receiving parties accept. If receiving parties simply receive and accept the unpaid offers which captured their attention, the aggregator will make no money. What a distorted map must do, therefore, is somehow redirect our attention away from the unpaid offers and toward the paid offers:

What distorted maps must do, therefore, is manipulate our attention costs as we receive offers so that unpaid offers waste our attention but paid offers conserve our attention. And because we use maps to conserve our scarce attention, this means that we’ll likely ‘choose’ the paid offers over the unpaid offers.

This effect is subtle, so it’s difficult to see and explain. One analogy, I suppose, is a company who optimizes the self-service component of their website but deliberately understaffs their call center (“We are currently experiencing delays – your expected wait time is 45 minutes …”) so that customers ‘choose’ to serve themselves on the web and save the company money.

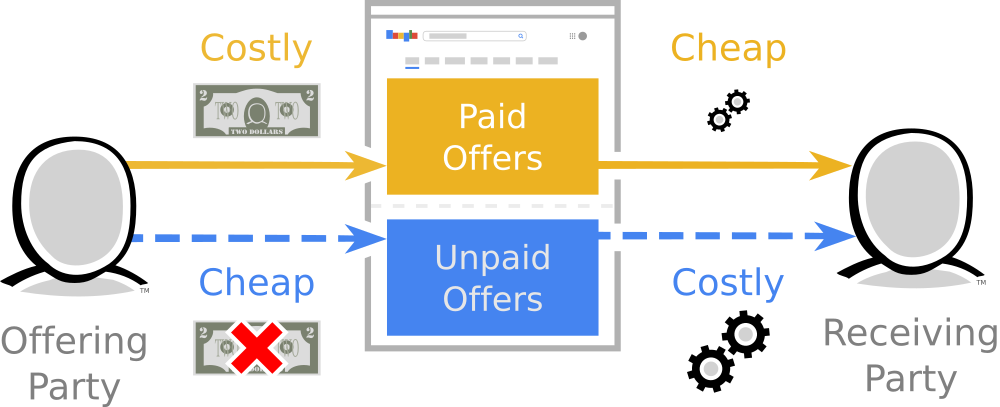

What distorted maps are doing, however, is manipulating receiving parties with a selfish choice architecture which forces offering parties to pay the aggregator. The offers which are cheap to offering parties (in terms of money) are made costly to receiving parties (in terms of attention) and vice versa, so that the receiving party ‘chooses’ the paid offer (and unwittingly forces offering parties to pay the aggregator):

It’s a classic ploy of intermediaries, in which the party who makes the choice does not suffer the cost of their choice. Credit card companies, for instance, maximize the convenience for buyers so that their ‘choice’ forces the vendor to pay fees to the credit card company. It’s the buyer, of course, who ends up covering the cost of these fees through higher prices, but there’s usually no way for them to pay less for cash and, therefore, no incentive to avoid the trap.

Perverse incentives

Distorted maps are a perverse balancing act – they lower the attention cost of receiving unpaid offers relative to competing maps (just enough to capture our attention away from them), but otherwise keep the attention cost for unpaid offers as high as possible so that we choose paid offers (and force vendors to pay the aggregator).

We don’t notice this, however, because new distorted maps (e.g. Google Search) must have a lower attention cost than incumbent maps (e.g. Yellow Pages directories) in order to capture attention away from them. New distorted maps, therefore, always feel like a generous gift and we fail to notice the attention costs that have been maintained in the unpaid offers.

Aggregators generating distorted maps have incentive to:

- compress the representation of unpaid offers (forcing receiving parties to waste attention to compare them),

- make faceted search weak or non-existent (to waste receiving party attention in comparing them),

- foster unnecessarily broad markets (so that paying the aggregator makes a difference and to maximize the competition to pay the aggregator).

The lie which distorted maps tell

The first lie which distorted maps tell about our economic territory is that:

The offers which make us the most money are the best offers for you.

The second lie is:

We represent every commercial offer.

This second lie is pernicious because it gives false hope. It implies that buyers can find every vendor and that every vendor can be found for free. The reality, however, is that the aggregator deliberately leaves unpaid offers in a congested mess so that we’ll choose the paid offers (and the aggregator gets paid by the vendor). Worse, there is no other kind of map that we can use to find unpaid commercial offers (until we build offerbots).

Footnotes:

- Google’s SERP is a distorted map when AdWords results (paid offers) appear on the SERP above and next to Search results (unpaid offers). This happens whenever offering parties bid for the keywords that the receiving party has used in Google Search or Google decides that a product advertisement is relevant to a receiving party’s search (http://www.google.com/ads/shopping/getstarted.html).

2. Yellow Pages directories were books which listed the telephone numbers of services providers in your city. They were published by the phone company and freely (and compulsorily) delivered to every home and business in the city. Every party who offered services in your city was given a free listing (which showed only their name, suburb and telephone number) and then encouraged to pay to make their entry larger (e.g. a quarter-page ad) or more attention-capturing (e.g. a bold title, coloured fonts, etc.). To help receiving parties navigate the map, services were grouped into categories and then sorted alphabetically by the name of the service provider (giving offering parties incentive to have names such as ‘AAAAAAAAAAA1 Painters’ in order to be listed first in the category). Because the categories were broad, there was also an index to help receiving parties work out which category their desired service fell into, and receiving parties were educated to go to the index first so that the directory was more convenient (and attention-capturing) to use.