Capitalism distributes wealth when markets are free and diverse. For hundreds of years, however, newspapers, television stations, supermarkets, shopping malls, search engines and other aggregators have facilitating our trade through centralized, homogeneous and distorted marketplaces, resulting in a poor distribution of wealth. Aggregators may be the single largest driver for inequality in our economy.

Capitalism

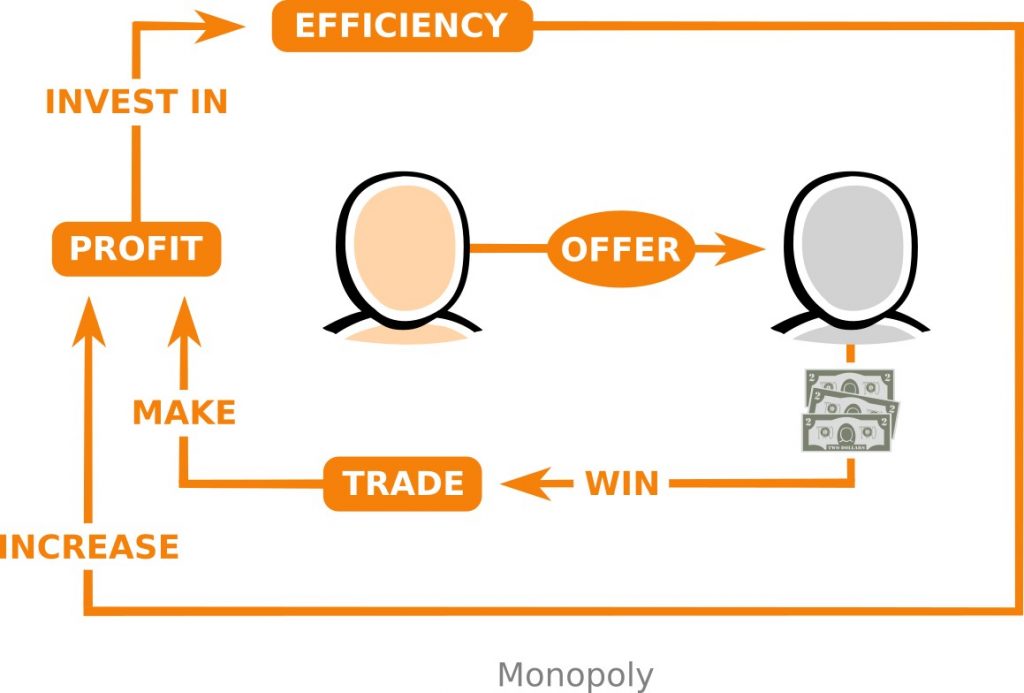

Capitalism is an economic system which allows us to increase our efficiency though trade:

Efficiency (which economists refer to as capital) is the ability to do more with your scarce resources (your time, energy, money and attention). In the loop above, we can see how this works.

The vendor (in orange) makes an offer to the buyer (in gray). If the buyer accepts the offer, they will trade the buyers’ money for whatever goods or services the vendor offered.

If this trade makes a profit for the vendor, they can then invest it in more efficiency. That could be investing in:

- tools (which allow you to achieve more with your attention, time and energy),

- training (a course, an online course, a book, etc.) to learn or improve a skill,

- staff (who are paid to help the vendor achieve more),

- training staff (to help them achieve more by increasing their efficiency),

- building relationships with partners or suppliers (through which you reduce your cost of goods),

- buying vehicles (which reduce waste in travel time and allow more time to be spent working), or

- a myriad of other efficiency-producing initiatives.

Finally the vendor may (or may not) pass on some of that efficiency on to buyers (to the public) by improving their offer, which could be either:

- reducing the price of their offer, or

- offering more to buyers for the same price.

This is how capitalism can increase the efficiency of the public (even for the people who don’t act as ‘vendors’, noting that employees are vendors of their time to a single buyer). That is, the entire populace benefits when vendors improve their offers (because this means that the general populace is able to achieve more with their scarce resources – their money, attention, time and energy).

The question is whether vendors will pass on their efficiency (as improved offers) or whether they’ll keep it all for themselves.

Monopoly

A monopoly is a market in which the vendor has no competition from other vendors. This means that the vendor is not forced to improve their offer (and share their efficiency with the public) but is able to keep it all for themselves if they wish:

That’s not to say that the vendor won’t improve their offer, but they must to be altruistic to give us their efficiency when there is no compulsion to do so.

The Free Market

In a genuinely free market, however, buyers have the freedom to choose. They can receive offers from multiple vendors and trade with whoever they see fit:

This means that we don’t need altruism from vendors to benefit the public – the free market forces even selfish people to improve their offers because each vendor’s offer must be competitive in order to be chosen by buyers.

With any positive feedback loop, however, there’s a significant danger that there will be inequality of outcomes:

Here the risk is that the orange vendor will obtain an effective monopoly, even when buyers can receive and consider the blue vendors’ offers. That’s because the positive feedback loop can concentrate small differences, allowing the orange vendor to go around the loop many times while the blue vendor does not. Over time this may allow the orange vendor to make vastly superior offers to the blue vendor (such that buyers always choose the orange vendor and never choose the blue vendor).

This outcome might appear to condemn capitalism and justify the seizure of the orange vendors’ efficiency to benefit the public. There is, however, an incredibly strong countervailing force which can overcome this kind of monopoly: diversity through creativity.

Diversity through creativity

Humans are diverse. We have different desires, different information, different resources and different kinds of efficiency to offer other people.

We’re also incredibly creative. We come up with incredible and unexpected solutions to problems.

If one vendor monopolizes the production of one commodity, therefore, other vendors can often find an alternate source of or substitute for that commodity.

If one vendor has a secret process, other vendors can often reverse engineer it.

If one vendor patents a process, other vendors can often find an alternative process.

If one vendor dominates a distribution channel, other vendors can often create a new one.

If one vendor makes a product which makes everyone somewhat happy, other vendors can often make a product which makes a subset of those people incredibly happy.

I could keep going, but you get the idea – whenever there’s a monopoly, you can often count on human diversity and creativity to find a way around it. This diversity and creativity, combined with market forces, is why our economy is more diverse and distributed than people like Karl Marx feared it would become [1], even when it’s less diverse and distributed that we need it to be.

More than that, however, the process of making and receiving offers must reflect this diversity of offers from vendors or this diversity will be lost – when offers appear to be the same, people will choose the cheapest one (and we get a race to the bottom which benefits the most efficient vendor).

And now we can identify the key conditions for capitalism.

The key conditions for capitalism

For capitalism to distribute the wealth it creates, we must have:

- genuinely free markets (and the competitive forces that they induce), and

- offer processing which represents the full diversity of offers made to us.

Aggregators, however, provide neither of these.

Aggregators are not free markets

As explained previously, aggregators do not create free markets, they are two-sided marketplaces which capture and sell attention.

Because they are not free markets, they do not have the characteristics and benefits of free markets as they connect buyers to sellers. They:

- distort price signals and, therefore, create over- or undersupply of goods and services,

- allocate trade to vendors create the highest profits for the aggregator (and are not chosen by buyers),

- create a private taxation system in which vendors are coerced to pay to access buyers (altering prices and demand),

- take profits and efficiency for themselves at our expense,

- monopolise attention and sell it at the highest possible price,

- exclude vendors who are unwilling or unable to pay, and more.

Aggregators homogenize markets

Aggregators are monopolies of attention which sell temporary monopolies (or oligopolies) to vendors.

This was explained in a previous article (Control), but we can extend the concept here. Firstly we can demonstrate that aggregators gain control by being effective monopolies in a similar way that vendors can become effective monopolies [2]:

That is, there is nothing which prevents the blue aggregator from generating and offering us maps, the problem is that the orange aggregator has gone around the cycle so many times that their maps provide significantly more convenience than the blue aggregator’s maps (such that we are free to use the blue aggregator’s maps but do not want to). Have you, for instance, felt like using the Yellow Pages recently?

The aggregator then sells a temporary monopoly to the vendor who provides the aggregator with the most money, allowing the vendor to go around the efficiency-creating cycle (and excluding the vendor who does not pay from that cycle):

This is why Google and others are sometimes referred to as kingmakers. If your business is blessed by their algorithms, you can enjoy outsized opportunities and profits (until the aggregator takes our opportunites and profits for themselves).

Note that there’s a paradox at work here, in that aggregators have significantly increased the diversity of our economy. But this diversity is leaked by the aggregator in order to capture our attention and, over the long term, will be recaptured by dominant aggregators.

To explain, each new aggregator must provide us with a greater access to a larger set of offers than current aggregators or we will not swap to the new aggregator. This increases vendor diversity but this is not the aggregator’s goal – their goal is to capture as much of the economy to their maps as possible which homogenises our trade and take our profits and opportunities for themselves.

- there are few aggregators that we use:

- because of the positive feedback loop (which destroys competition for aggregators),

- resulting in few algorithms for the attention-capturing side (to benefit beneficiaries) e.g. newsworthyness, popularity, engagement, attractiveness, etc., and

- resulting in aggregators replacing us as vendors (fewer vendors, greater concentration of wealth)

- only one algorithm for selling attention across all aggregators – highest bidder (positive feedback loop – the tail wags the dog)

- broad markets / compression of offers used to maximise competition between vendors (stripping diversity from offers)

- missing opportunity from opportunities aggregators haven’t noticed (or can’t monetize),

- stripping opportunity across the economy.

The Four-Tier Economy

Putting all this together, then, you and I trade in an economy which consists of four tiers:

- Aggregators,

- Beneficiaries,

- Vassals, and

- The Excluded.

Aggregators

Aggregators capture and sell our attention in order to take a proportion of the value we exchange when we trade. This aggregation makes these corporations some of the most valuable in our economy.

Beneficiaries

Beneficiaries are the offering parties who can freely or inexpensively make offers through the aggregators (because it benefits the aggregator to let them do so). Examples include:

- the vendors at the top of Google Search,

- companies who can create amusing advertising content (which is shared across social networks), and

- anchor stores who pay relatively little (per square meter) to be represented in shopping malls (and are physically separated from other anchor stores to minimize competition).

Vassals

Vassals are the offering parties who must pay a significant proportion of their margins to aggregators to participate in trade. Examples include:

- small businesses who must compete in Google’s AdWords auction to be found by prospective clients in Google Search,

- manufacturers who have little power relative to supermarkets (and are forced to reduce their prices, bear the supermarket’s costs and risks and, sometimes, pay significant listing fees),

- small retailers in shopping malls (who pay large rents indexed to their revenue and suffer competition by being colocated with their competitors).

The Excluded

The Excluded are everyone else. The people whose offers are not represented on any map from any aggregator because:

- their offer doesn’t benefit the aggregator (to be a beneficiary),

- they can’t outbid other vendors (to be a vassal), or, quite simply,

- there is no map available to represent their offers.

Examples include:

- ‘consumers’ (who apparently have nothing to offer anyone other than their labor in employment),

- everyone in developing countries (when trying to reach customers in developed countries)

The beneficiaries are arbitrary

To capture receiving party attention, aggregates frequently represent some offers in maps without requiring payment from the offering parties. Think, for instance, of the businesses whose offers appear at the top of Google Search results or the amusing television commercials which are shared by users on Facebook. The offering parties who benefit from this free exposure for their offers are beneficiaries.

Beneficiaries become vassals

the underclass of people whose offers are not represented on aggregators’ maps, because:

- the aggregators’ algorithms reject them as potential beneficiaries, and

- they’re outbid (by other offering parties) in their attempt to be vassals.

Think, for instance, of sub-Saharan Africans (who are too poor to capture or buy anyone’s attention) or so-called consumers (who cannot make offers but merely receive them). In theory, offer-processing corporations would like The Excluded to become vassals (so that they can make money from them as well), but in practice they must exist to force vassals to pay (lest they also become excluded).

Homogeneity drives competition between vendors to pay the aggregator – thick (homogenous) markets in which people compete the most for advertising. Google Search not filtering products and services.

Small vendors pay more

These are the offering parties who manage to purchase receiving party attention for their offers, sometimes at such a high cost that the majority of their margins go to the aggregator. Think, for instance, of small businesses who must compete to buy AdWords advertising or small retailers who must pay high rents in shopping malls (when larger businesses are get free exposure on Google Search or low-cost ‘anchor store’ rents in shopping malls).

You can see this clearly in this letter which Google sent to Australian small businesses in 2012 (the highlight is mine):

Did you see it? Google told small businesses that they were unlikely to send prospective customers in their direction. The ‘good news’ is that the small business can become Google’s vassal by purchasing AdWords advertising (by competing in an auction against all of the other small businesses who are unlikely to trade with prospective customers through Google).

The only winners are aggregators

Aggregators want to turn beneficiaries into vassals. That is, they don’t want to give away free opportunity – they will do everything they can to force offering parties to pay them.

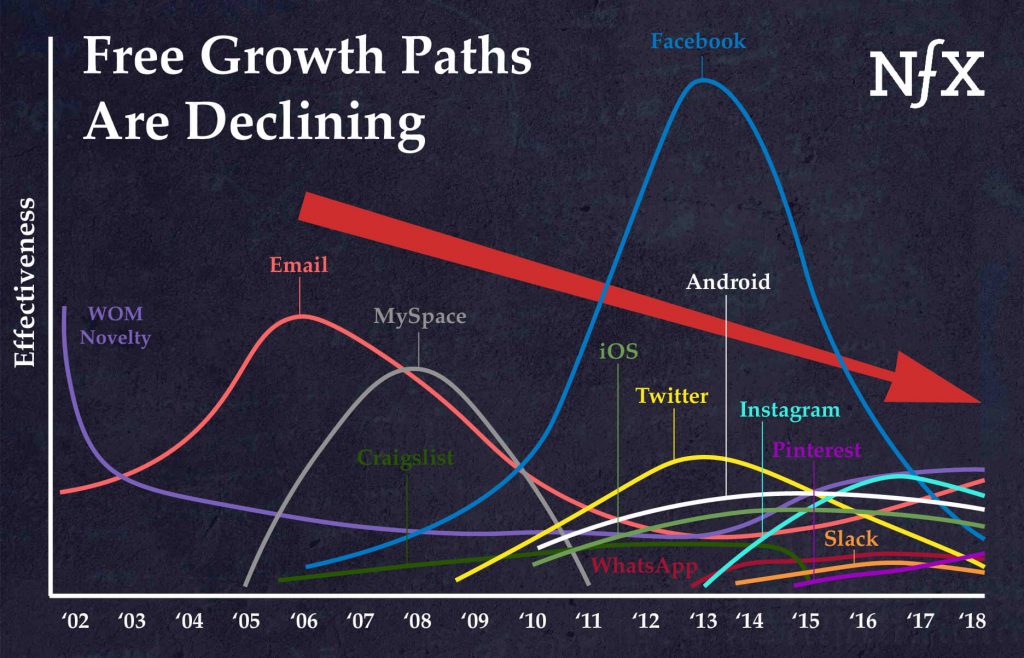

This diagram from NfX shows how successful aggregators are at doing this:

That is, all of the curves (except ‘Word Of Mouth’) initially go up, indicating that there is opportunity for offering parties to have their offers represented for free.

New aggregators make many people beneficiaries in order to overcome the ‘chicken and egg’ problem of starting a two-sided marketplaces. They giveoffering parties a free ride so that their maps will contain offers which attract receiving parties (a process which is called supply-side hacking).

You can see, however, that all of the curves then go down, indicating that offering parties now need to pay in order to trade in that marketplace. Once the aggregator has captured receiving party attention, however, the aggregator can start ‘monetizing’ their attention by closing down the free opportunities (turning beneficiaries into vassals).

Put simply, it’s a trap. Initially the Yellow Pages touted free advertising (instead of expensive newspaper ads) but it became so crowded that you had to pay thousands of dollars to stand out. Google promised you’d be found on Search but now you’re on page 6 of search results and you’re forced to buy AdWords advertising at $10 per click. The same goes for Craigslist, Facebook, Twitter, Instagram and so on – each of us believed that we’d finally found a free place to do business, only to discover that it became expensive to reach their customer base with our offers.

This is how Marissa Mayer described Google’s approach to creating new products back in 2006:

“A lot of people will say, “Well, aren’t you [Google] worried as you roll out new products, you know, will there be a business model there, you know with all this innovation?” And to be honest, we don’t really worry about that. We worry a lot about whether or not we have users, but we don’t worry a lot about business models in the beginning, because it turns out, especially on the Web, and especially with consumer products, money follows consumers. The consumers may choose to subscribe to things themselves. Advertisers also follow consumers, so if you manage to amass huge amount of users and you’re doing something that they use every single day, you’ll find a way to monetize it.”

In other words, Google gives away various kinds of offer processing but the goal is (and always will be) to ‘monetize it’.

The aggregation paradox

Defenders of aggregators are looking at the wrong timescale.

In the short term aggregators create enormous opportunity. In the long term they capture it for themselves.

Amazon creates many jobs. Unfortunately those jobs treat the workers like robots (until Amazon can replace them with robots).

Google gave small businesses opportunity which mass media had taken away (by maximizing the price of their advertising). Now Google captures the profit

Facebook is helping countless small businesses to find customers.

Instagram helps people start businesses selling anything which looks appealing in a photo.

Tinder helps you filter people based on their appearance so that you can sleep with someone you find attractive tonight.

Facebook commissioned a report from Copenhagen Economics showing the economic benefits that the aggregator has brought to Europe (where Facebook faces its most significant opposition from government).

The jobs you can see are a tiny subset of the jobs you can’t see.

Return to Collateral Damage

Footnotes:

- Human diversity and creativity is the reason that our economy is so much more diverse and distributed than the was understood and described by Karl Marx in 1848. It turns out that the 1800s wasn’t the pinnacle of capitalism and that human creativity, combined with market forces, resulted in an rich diversity of efficient technologies and a reasonably broad distribution of them (45% of the world has a computer in their pocket!). If the proletariat had seized the means of production from the bourgeoisie in the late 1800s we might still be making the same set of products from the late 1800s using the same set of manufacturing technologies. I strongly suspect, however, that human diversity and creativity would have found a way to bypass that form of political economy as well.

- Aggregators may be a special case in the economy in which it is prudent to intervene in the market and create regulations which apply brakes to the feedback loop. It seems unwise, for instance, to allow aggregators to reinvest all of their gross profit in efficiency (as Amazon does) without paying tax. That is, governments should recognize that an aggregator’s investment in efficiency is buying control for shareholders and that this is a form of wealth extraction for shareholders which should be taxable (as paying dividends is).